Book Project

Prisons and Profits: The Political Economy of Race and Incarceration in the Postbellum American South

When the Confederate army surrendered to Union troops in April 1865, one of the bloodiest war the world had seen to date finally ended, freeing approximately 3.9 million African Americans who were formerly enslaved in the American South. However, their “moment under the sun”, as W.E.B. Du Bois famously put it, was short-lived. Almost immediately after the war, Southern elites began to alter penal laws and institutions to facilitate the large-scale incarceration of freedmen and -women. In the decades that followed, tens of thousands of African Americans were convicted, often on dubious grounds and trumped up charges.

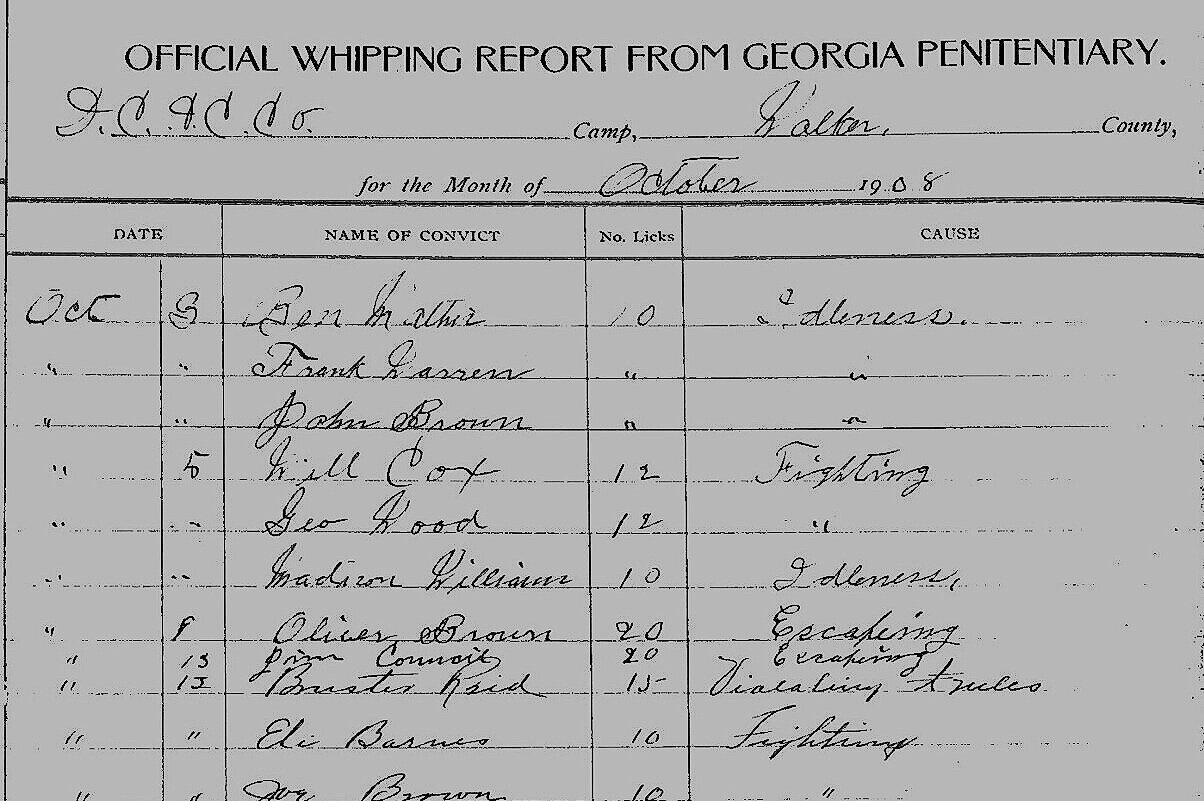

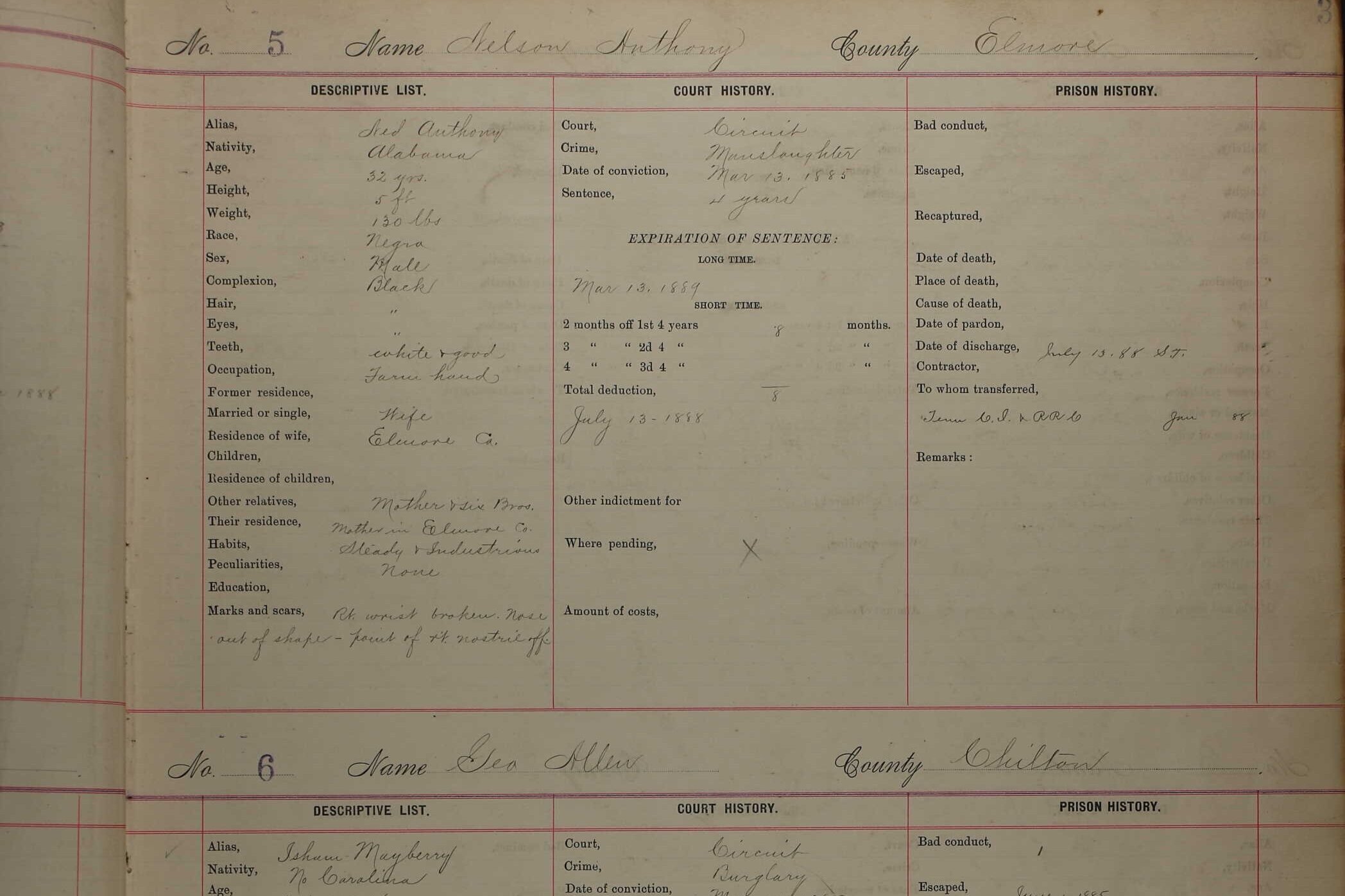

However, unlike Northern states where prisoners served their sentences in designated penitentiaries, the South introduced a distinct mode of punishment: the convict leasing system. Under this system, inmates were no longer confined within state-owned prison walls. Rather, governments rented out their prisoners to private individuals and companies for a fee, removing most of the state’s oversight of inmate treatment and care. Private entities were responsible for housing and feeding inmates and for providing them with clothes and medical services. In return, prisoners were coerced to work for their lessees for the duration of their sentence—on railroads and plantations, in coal mines, brickyards, and lumber camps all over the South.

In my dissertation and book project, I seek to understand the role that penal institutions, in particular convict leasing systems, played in Southern statebuilding processes in the decades after the Civil War. In the first part of the book project, I investigate the political origins of convict leasing in the American South after the Civil War. I argue that convict lease systems were first introduced at a time when Southern states created rapid growth in incarceration but had neither the carceral infrastructure nor the funds to build prisons to respond to their rising “prisoner problem.” Using a case study approach, I find that convict leasing often emerged from these challenges as a bipartisan project because it offered a cost-neutral alternative to conventional imprisonment.

In the second part of the book project, I show how convict leasing became an important public finance instrument after Reconstruction as states began to collect increasing shares of their annual revenue from contracting out their prison populations. In particular, I test to what extent states used convict leasing, through increased incarceration, as a means to counter short-term revenue fluctuations—a fiscal practice I call “revenue smoothing.” Consistent with this argument, I show that states increased their conviction numbers in years following declines in revenue growth. As such, Southern states strategically repurposed antebellum institutions of coercive labor to consolidate their post-war public finance when public support for other statebuilding instruments such as taxation was limited.

The empirical components of this project draw on a range of data and evidence that I collected during several field visits to Southern state archives. As the cornerstone of my dissertation, I have been collecting an original dataset on Postbellum Incarceration in the American South (PIAS) from handwritten, historical prison admission records. So far, PIAS database details close to 120,000 convictions across eight Southern states between 1817 and 1920. In my analyses, I combine PIAS data with existing datasets on 19th-century state public finance. In addition, I rely on numerous primary sources, including agency reports, executive minutes, prison correspondence, and newspaper coverage, chronicling Southern prison operations in the postbellum decades.